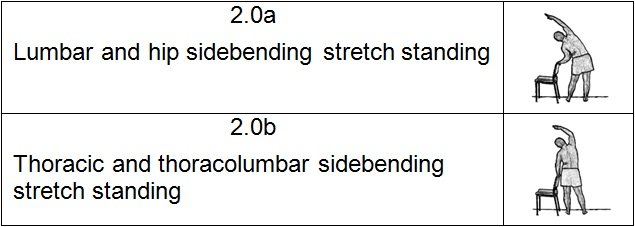

2.0 Chair supported thoracic, lumbar & hip active sidebends

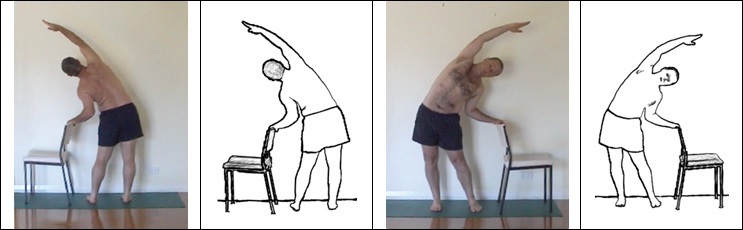

2.0a Lumbar and hip sidebending stretch standing

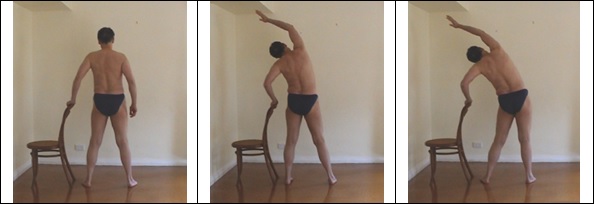

Starting position

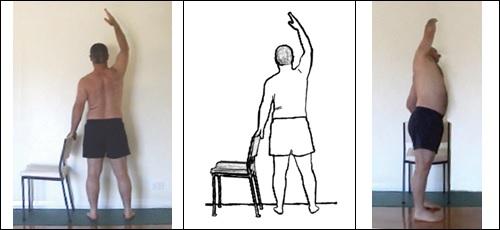

- Stand with the left side of your body near to the back of the chair.

- Grasp the back of the chair with your left hand.

- Raise your right arm sideways until it is nearly vertical.

- Use the back of the chair as a pivot, and for support and control.

- Both legs remain extended – do not bend your knees.

- Your body is in the frontal plane – do not rotate your pelvis or spine.

- Your centre of gravity falls evenly across both feet – for ideal balance.

- Sideshift your pelvis and hips to the right and away from the chair.

- Flex your left elbow to lower your body and sidebend your spine left.

- Stop when you feel the initial stages of a stretch down your right side.

Technique

- Take a deep breath in.

- Exhale and reach 45 degrees up and to the left with your right arm.

- Keep your right elbow extended and reach strongly with your fingertips.

- Feel you are lengthening the spine rather than compressing it.

- Hold the stretch for about five seconds or the length of a full exhalation.

- Breathe in again.

- Flex your left elbow to sidebend your body further to the left.

- Stop when you feel the resistance again down the side of your body.

- Hold this position and repeat the stretch on the right side of your body.

- Repeat the stretch for the left side of the lumbar spine.

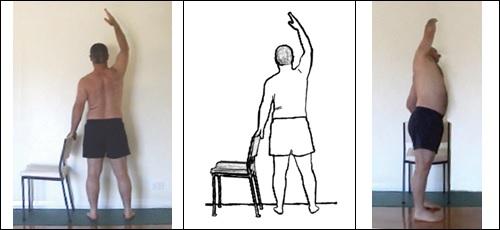

Part B. 2.0 Chair supported thoracic, lumbar & hip active sidebends

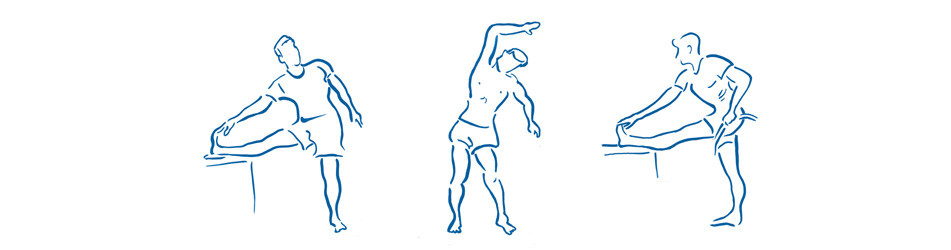

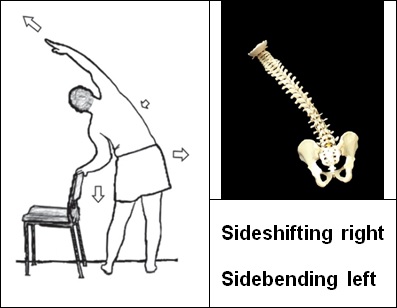

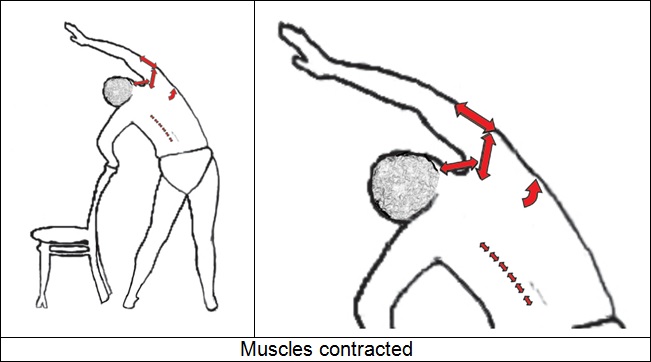

Starting position: Standing and grasping the back of a chair with your left hand. Use the chair as a pivot and for support and control. Raise your right arm to the vertical position. Keep your legs straight, your weight evenly balanced on both feet and your body in the coronal plane. Flex your left elbow to sidebend your spine left but stop when you start to feel a stretch down your right side.

Technique: Take a deep breath in. For a localised stretch of your right lumbar spine: sideshift your pelvis to the right (away from the chair); exhale and reach 45 degrees up and to the left with your right arm; keep your right arm straight and reach with your fingertips.

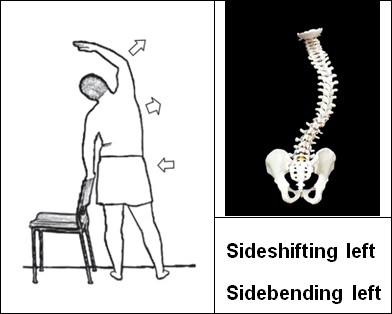

For a localised stretch of your right thoracic spine: sideshift your pelvis to the left (towards the chair); flex your right forearm 90 degrees; point the tip of your right elbow 45 degrees up and to the right; exhale and sidebend your thoracic spine and ribs to the left by sideshifting your upper thoracic spine and ribs to the right (away from the chair).

Hold the stretch for about 5 seconds or the length of a full exhalation. Flex your left elbow to sidebend your spine further to the left. Hold this position and then repeat the stretch several times for the right side of your body. Repeat the stretch for the left side of the spine.

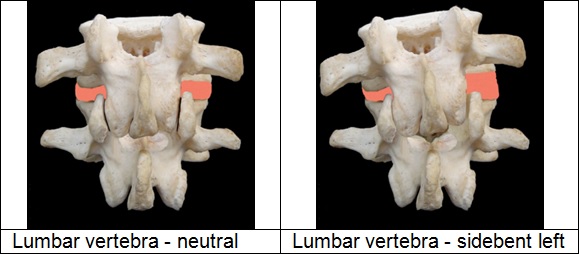

Direction and range of movement

Thoracic sidebending to one side is about 20 degrees. Lumbar sidebending to one side is about 30 degrees. Most sidebending in the lumbar occurs in the middle lumbar and the least sidebending occurs at the lumbar sacral spine.

The back of the chair is important for enabling you to have control over the stretch. It supports your body weight and also acts as a pivot. By adjusting the amount of sidebending of the spine and sideshifting of the pelvis and/or the upper torso the sidebending stretch can localised to different areas of the spine.

Sidebending is produced by increasing the amount of flexion of the elbow closest to the chair, while sideshifting is produced by moving the pelvis way from or toward the chair. Sideshifting the upper torso in the opposite direction to the sideshifting of the pelvis can be useful for more emphatic localisation.

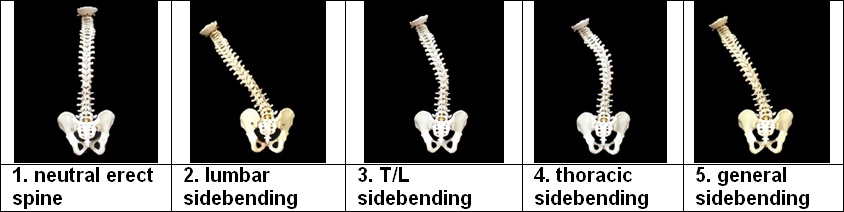

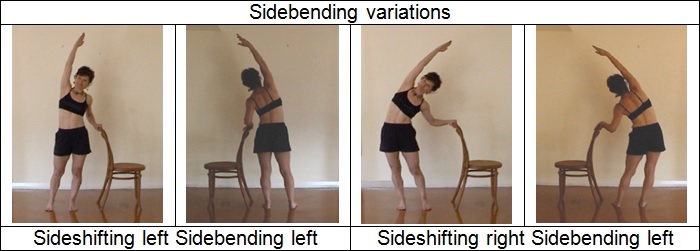

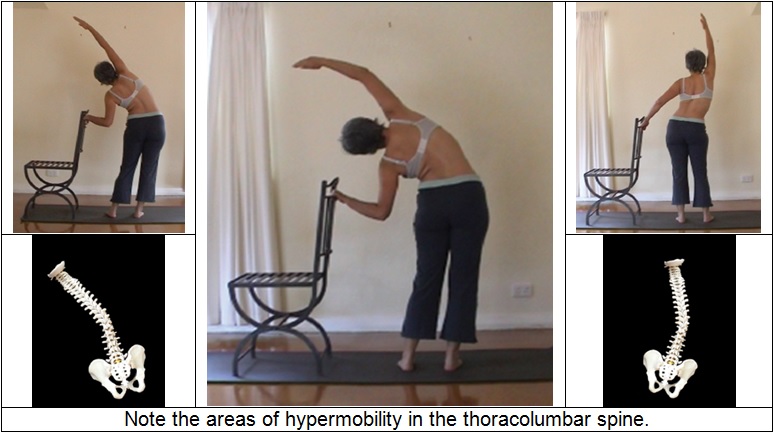

Increasing the amount of lateral pelvic movement or sideshifting away from the chair (as in stretch 2.0a) results in greater lower lumbar sidebending and less thoracic sidebending – the thoracic spine remains relatively straight (see image 2).

With little to no sideshifting, greater emphasis is placed on sidebending of the upper lumbar spine or the thoracolumbar region (see image 3).

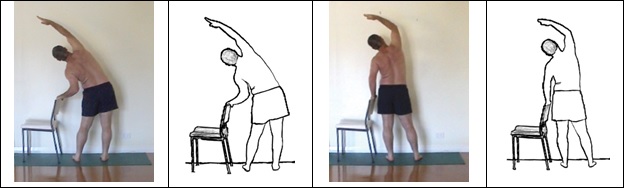

Increasing lateral pelvic movement or sideshifting towards the chair (as in stretch 2.0b) results in greater middle and lower thoracic sidebending and less lumbar sidebending – the lumbar spine remains relatively straight. Even greater thoracic sidebending is achieved by combining this lateral pelvic movement with upper torso sideshifting away from the chair (see image 4).

A generalised sidebending of the spine is possible with moderate amounts of sideshifting away from the chair (see image 5). Generalised sidebending or targeted sidebending is recommended to avoid exaggerating areas of hypermobility in the thoracic or lumbar spine.

If you know the state of your spine, with regard to its structure and mobility, then you should targeted those areas in the spine where there is restricted sidebending and avoid overstretching area where there is hypermobility.

If you don’t know the state of your spine then focus on generalised sidebending, placing greater emphasis on lengthening the spine and less emphasis on increasing sidebending.

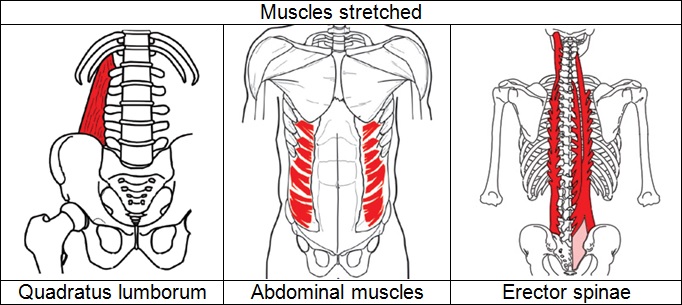

Target tissues

Stretching primarily occurs in the lateral abdominal muscles, quadratus lumborum, and the lateral fibres of the erector spinae – the iliocostalis lumborum and thoracis. These muscles are anchored onto the iliac crest and attach on ribs above.

This is also a good stretch for the intercostal muscles, psoas, latissimus dorsi, thoracolumbar fascia, teres major, lower fibres of pectoralis major, lateral fascia of the hip, lateral ligaments of the spine, tensor fasciae latae, gluteus medius and the upper fibres of gluteus maximus. This is a mild stretch for teres minor, the lower fibres of posterior deltoid and the long heads of biceps and triceps.

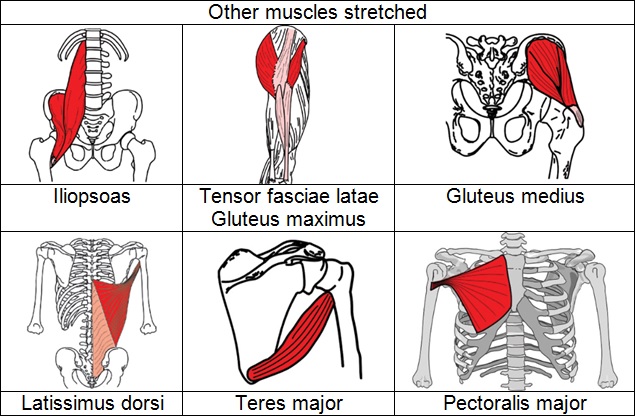

Although there is a passive component to this technique this is mainly an active stretch. The passive component uses gravity and the weight of the upper body, which is controlled by flexing the elbow nearest the chair and lowering the upper body to the side.

This is a very dynamic stretch with the active component of the technique involving shoulder muscle contraction to increase the intensity of the stretch, thus increasing the number of muscles stretched. The shoulder muscles are also engaged so that the stretch occurs broadly across many vertebral levels and does not focus solely on small single spinal muscles such as the deep rotators. For safety reasons the stretch should be spread across many muscles and tissues, including lower trapezius, latissimus dorsi, quadratus lumborum and the thoracolumbar fascia.

Supraspinatus, middle deltoid, trapezius and serratus anterior actively contract to abduct the scapula and shoulder, thereby stretching muscles such as latissimus dorsi and lower fibres of pectoralis major.

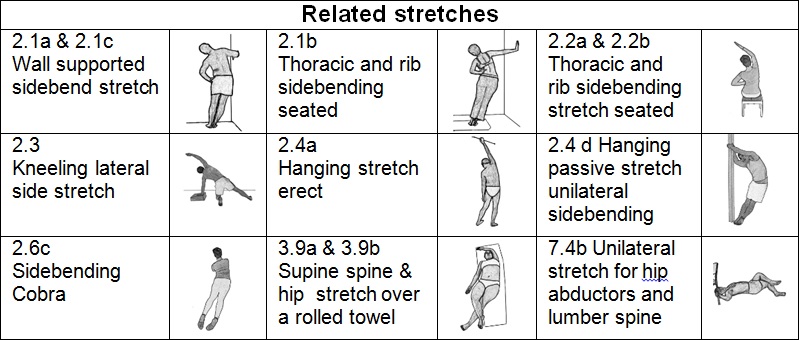

Variations

As an alternative to using a chair other objects can be used for support. These include a table, bench, wall, gate or a fence. A wire mesh fence, such as is used at a tennis court provides a very useful support because you can grasp the wire mesh with both hands and use it to localise sidebending.

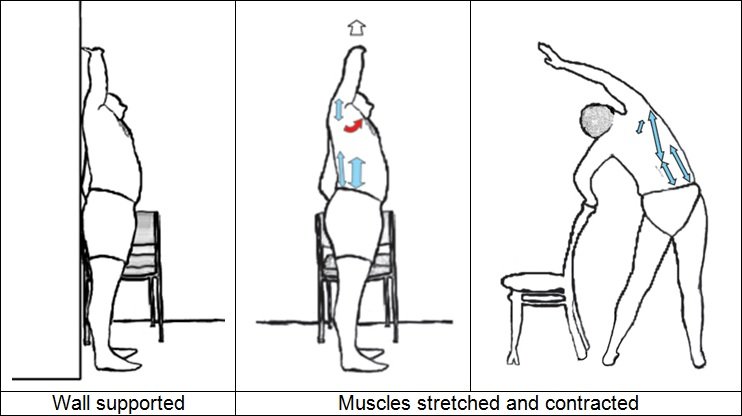

This technique can be also done with your back in contact with a wall, which provides postural feedback to enable you to keep your body squarely in the coronal plane (also known as the frontal plane), assisting in maintaining better alignment during the stretch.

Technique

- Stand with your buttocks, back of your spine and rib cage against a wall.

- Place the backs of your heels 3 cm away from the wall for optimal balance.

- Grasp the back of a chair with your left hand and sideshift your pelvis (to the right for stretching the lumbar or to the left for stretching the lower thoracic), while sidebending your spine to the left to localise your stretch.

- Raise your right arm above your head and reach over your head.

- Keep the tip of your right thumb in contact with the wall during the stretch.

- Keep your back and other contact points in contact with the wall.

Another option is to stand near the corner of a room with your back against one wall for feedback and use the other wall for support and control.

Safety

If you have a scoliosis and know where in the spine it is and which direction it is sidebent, you can use this stretch to counter the scoliosis. Also if you have areas in your spine that are either stiff (hypomobile) and/or hypermobile you can taylor the stretch to the situation with greater and more focused stretching in the stiff areas and avoiding stretching the hypermobile areas.

If you are not aware of the structure of your thoracic and lumbar spine then you should do this technique as a generalised stretch, and not try to force sidebending in any single part of your spine.

Down each side of the vertebral column are many small muscles traversing one to three vertebral segments. Individually these muscles are relatively weak and can be strained if strong forces are used to sidebend the spine. You should try to spread the stretch across many vertebrae, thereby including larger muscle groups, as well as multiple muscle layers.

By stretching through the shoulder and involving lower trapezius, latissimus dorsi, quadratus lumborum and the thoracolumbar fascia, this technique is made much safer. You should feel like you are pulling your arm out of its socket, thereby lengthening the spine with traction, rather than squashing it with compression.

A safer stretch will cause less strain on vulnerable muscles and ligaments and less compression on intervertebral discs. Intervertebral discs are able to withstand normal sidebending movements; in fact healthy intervertebral discs will benefit from moderate lateral compression forces. But the combination of overstretching and pre-existing disc disease may result in a disc bulge and nerve root irritation. As one cannot predict the outcome of any stretching exercise, safety is always the best option.

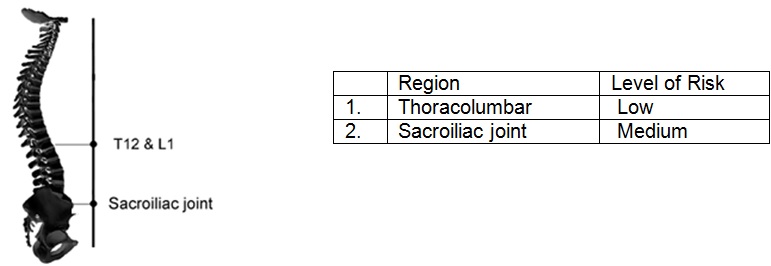

Care should be taken not to overstretch the spine if areas of localised hypermobility are identified. Hypermobility can exist in any area of the body, but more commonly it exists in the spine, particularly in the suboccipital, lower thoracic, thoracolumbar and sacroiliac spine. Stretching hypermobile areas may exaggerate the hypermobility, leading to muscle and ligament strain.

Vulnerable areas

Key